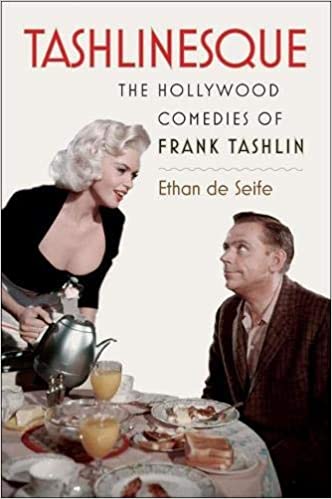

TASHLINESQUE: The Hollywood Comedies of Frank Tashlin. Ethan de Seife. Wesleyan University Press 280pp

In the annals of the Hollywood comedy, the director Frank Tashlin’s films create a place of their own, inhabiting a world at once ribald and delightfully impolite. Tashlin’s landscape is lively, politically and culturally savvy – from his romps with Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis bumbling across the United States in Hollywood or Bust (1956), to Jayne Mansfield and Tom Ewell’s sweet-natured repartee in The Girl Can’t Help It (1956), up to the befuddled angst just hanging off Tony Randall’s face as he shares the frame with Mansfield in Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? (1957), Tashlin’s on-the-money spoof of the 1950s American advertising industry. Even Tashlin’s less successful work has its moments of gutsy humor – who can ever forget the mighty little dachshund trying to drag a huge dinosaur bone across the Santa Monica beach in Bachelor Flat (1962)?

With all this good-natured action inside the frame, Tashlin’s Hollywood comedies of the 1950s and 60s looked as if they were shielding American audiences from the social world outside the movie theatre, from the burgeoning Civil Rights movement to the breakdown of the Hollywood studio system itself. Tashlin’s films are smart spoofs on their targets: sexual mores, big business and the search for a few minutes of cultural celebrity. For giving audiences this kind of witty entertainment, one might think that Tashlin would enjoy a weighty reputation, given our twentyfirst-century mania for Hollywood nostalgia.

Yet, as Ethan de Seife reminds us in his precise and non-humorous study of Tashlin, Tashlinesque, Tashlin is for the most part one of Hollywood’s forgotten men. The word “Tashlinesque” was used by the young critic-film director Jean-Luc Godard in 1958 in Cahiers du Cinema. As de Seife tells us, Godard noted that Tashlin didn’t “renew” the older, sophisticated Hollywood comedy but instead “created” it again. But that praise went unnoticed in Hollywood. Over filly years later, Frank Tashlin’s name barely reaches beyond a community of film critics.

Wanting to give Tashlin his critical due, de Seife moves appreciatively and thoroughly through all phases of the director’s art and career. The book is detailed but stylistically dry. The result is a stilted but nevertheless very much needed close study of Tashlin’s great contribution to the Hollywood comedy.

Affectionately known as “Tish Tash” in Hollywood circles – the name by which he produced a short-lived comic strip, “Von Boring (He Never Said a Word”) in the mid- 1930s – Tashlin navigated a successful and multi-layered career in animation during the 1930s and 40s, creating some of the best of the Warner Bros. Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies series and introducing in them cinematic techniques such as off-kilter camera angles, montage and quick pacing. He then successfully moved into directing live-action features in the late 1940s, soon directing Bob Hope and Jane Russell in Son of Paleface (1952). His work with Martin and Lewis, and later his lunacy with the solo Lewis, was serendipitous. He called Lewis his muse and Lewis returned the flavor. Tashlin directed some of Lewis’s best-known comedies: Geisha Boy, Cinderfella, The Disorderly Orderly. It was hard, many said, to know where Lewis left off and Tashlin began.

As de Seife notes, Tashlin hit an even higher peak when he directed the bombshell Jayne Mansfield in her two best-known outings, The Girl Can’t Help It and Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?. Mansfield’s magic mix of brassy sexuality and supreme warmth coupled with Tom Ewell’s deadpan face and Tony Randall’s complete exasperation-turned-desperation, secured these two comedies Tashlin’s permanent place in Hollywood history. His slapstick moments, floating briefly as they do in some of the films, display a cleverness and an unadulterated joy in being alive. Tashlin choreographed (and often wrote) a world that sped up the Hollywood comedy.

De Seife’s book concentrates on Tashlin’s technical genius; he explains it succinctly. Yet his dead pan language cannot fully embrace the director’s joyous ribaldry. Nevertheless, the book is insightful (although it could have done with a photo of Tashlin’s wonderful face somewhere in these pages) and views Tashlin from within the context of other directors of the time, such as Howard Hawks and Norman Taurog, and even Billy Wilder.

TLS (Times Literary Supplement), November 16, 2012